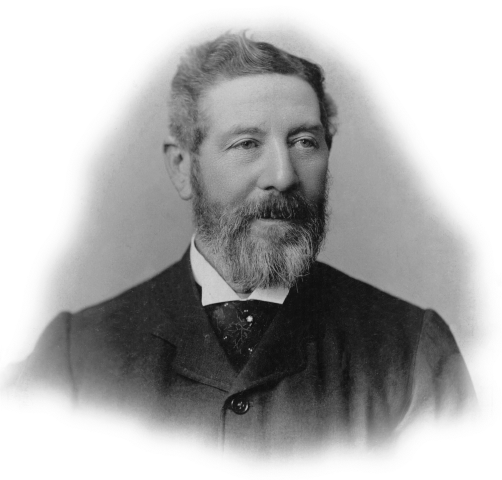

James Oliver of Hartington 1835-1922

James Oliver of Hartington 1835-1922

& the Dramatic Tale of his near Shipwreck 1857

A Hartington History Group Occasional Paper by Richard Gregory

The rewarding and eventful life of James began as the second son of Robert and Elizabeth Oliver, born in Hartington and brought up at Nettletor Farm. His elder brother, William Jacob Oliver, was born in 1829 and a sister Harriet was born in 1840. He was related [first cousin once removed] to John Oliver [1856 – 1927], also born in Hartington and who grew up to serve as Prime Minister of British Columbia, Canada, from 1918 – 1927.

At the age of 15 James was apprenticed to the drapery business in Burslem, Stoke-on-Trent, in the sum of £70 for six years inclusive of tuition, full board, clothing and medical expenses. Upon completing his term he decided to emigrate to Canada but never reached that land; having almost missed his departing ship at Liverpool, the Martin Luther, he was then close to being ship-wrecked during a violent storm which swept the vessel towards the Isle of Ushant, off the western tip of Brittany, before being taken in tow. The ship was taken to Plymouth and James returned home, unsurprisingly having abandoned his plans to emigrate. [See below the story of this terrifying adventure, written by James].

Initially, James appears to have re-engaged with the drapery business, being present on the 1861 census day at an address in Limehouse, Tower Hamlets, London, where his occupation was described as ‘Draper’. This also happened to be the address of his future wife, Elizabeth Dorothy Staley, and in-laws; indeed, it was probably around this time that they were married. Following their marriage they settled in Hartington and over time James developed his multi-faceted roles of Auctioneer, Probate and Tenant Right Valuer, and Estate Agent. He also ran an insurance agency representing The Royal Insurance Company, The Norwich & London Accident Insurance Association, and The Horse, Carriage and General Insurance Company. Obviously he was still short of things to do because he added another agency, for Brown & Wilson, Seed Merchants of Manchester. In 1879 James was elected to the Ashbourne Board of Guardians representing Hartington Town Quarter, for which area he was also the representative on Ashbourne Rural Council. He was known for his punctilious and conscientious approach to his civic duties, one example being his attendance at the Ashbourne Rural Council meeting on a wintry day, 21st January 1922, at the age of 86. This was just six days before his death on the 27th, having been taken ill on the 24th. James had long been a Wesleyan local preacher and preached at Hartington Chapel on the 22nd January. Although a Non-conformist he regularly exercised his privileges as a communicant of the Church of England and, it is said, was a friend to all, regardless of sect, especially in times of sickness or other difficulty.

James and Elizabeth Dorothy [in her youth her name may have been shortened to Dora] became parents to six children and resided at Nettletor Farm, Hartington, then later at Springfield House. In 1884, across the road from Springfield on the other side of the mere [‘duck-pond’], James built Staley Cottages at a cost of £200 each, still owned by the Oliver family [2018].

Census information

provides further background to James’ family circumstances.

1841 The family address is written as Gerpe Lane, Hartington.

Robert Oliver, age 40, born 1801.

His wife Elizabeth Oliver, age 35, born 1806.

Son William Oliver, age 12, born 1829.

Son James Oliver, age 6, born 1835.

Daughter Harriett Oliver, age 0, born 1841.

All recorded as being born in ‘Derbyshire’.

James’ mother Elizabeth died in 1849.

1851 Township of Burslem, Borough of Stoke-on-Trent, [?]5 Market Place.

John Thomas Smith, Head, Foreman Draper, 39 [or 29], born Derbyshire, Ashbourne.

Various assistants/apprentices including James Oliver, 15, born Derbyshire, Martington.

The census enumerator probably misheard ‘Hartington’ as ‘Martington’.

1861 Parish of Limehouse, Borough of Tower Hamlets, 3 ?

George Staley, Head, 63, born Derby, Pentrich.

Maria Staley, Wife, 54, born Derby, Pentrich.

Dora Staley, Daughter, 22, born Middlesex, Stepney.

James Oliver, Visitor, 26, Draper, born Derby, Hartington

[+ three sons and a servant].

In 1871 the given address is Nettletor, Hartington.

Robert Oliver, age 74, born 1797, head of household.

Son William Jacob Oliver, age 42, born 1829.

Son James Oliver, age 35, born 1836.

Daughter-in-law Elizabeth Dorothy Oliver, age 33, born 1838.

Grandson Harold Oliver, age 8, born 1863.

Grandson Sidney Oliver, age 6, born 1865.

Grand-daughter Edith Oliver, age 1, born 1870.

All are recorded as being born in ‘Derbyshire’, except for Elizabeth Dorothy, given as ‘London’. Robert’s age and birth date contradicts the details in the 1841 census, but a family tree gives the date 1797. He died in 1875. Harold’s birth record shows 1862, here it is recorded as 1863 and in the 1891 census it is written as 1864. Similarly James’ birth date is given here as 1836, not 1835, and Sidney’s birth date should be 1864. Census details like these are often inaccurately recorded.

The 1881 census records the address as ‘Hartington Nettleton’.

William Jacob Oliver, age 52, born 1829, head of household.

Brother James Oliver, age 45, born 1836.

Sister-in-law Elizabeth Dorothy Oliver, age 42, born 1839.

Nephew Sidney Oliver, age 16, born 1865.

Niece Edith Oliver, age 12, born 1869.

Nephew Leonard Oliver, age 10, born 1871.

Nephew Robert Oliver, age 5, born 1876.

Nephew William Oliver, age 0, born 1881.

Again, birthplaces are given as ‘Derbyshire’, with the one exception, ‘London’. William Jacob did not marry and died in 1885. Presumably James and Elizabeth’s eldest son Harold was elsewhere on census day, as he is absent from the record [he has not been found on any other census record for 1881].

The 1891 census return records the address as ‘Nettletor Farm, Littlewood, Hartington’.

James Oliver, age 55, born 1836, head of household.

Wife Elizabeth Dorothy Oliver, age 53, born 1838.

Son Robert Oliver, age 15, born 1876.

Son William Oliver, age 10, born 1881.

In this year given birthplaces were more specific, written as ‘Hartington’, or in Elizabeth’s case as ‘Stepney, Middlesex’. Only two of the six children were at home on census day in 1891. Sidney had emigrated to Canada in 1885 or thereabouts, Leonard’s whereabouts do not show up in that year’s census, while Harold kept the ‘Charles Cotton Hotel, Littlewood’ as ‘Hotel Keeper and Brewer’s Agent’, assisted by his sister Edith as ‘Housekeeper’.

In 1901 the census records the address as ‘Springfield, Dig Street, Hartington’.

James Oliver, age 65, born 1836, head of household.

Wife Elizabeth Dorothy Oliver, age 62, born 1839.

Daughter Edith Oliver, age 37, born 1870.

Son Leonard Oliver, age 29, born 1872.

Son William Oliver, age 20, born 1881.

Grandson Edgar Oliver, age 4, born 1897.

Edith was now ‘back home’ with her son Edgar. She never married and Edgar was her only child. Harold was still at the Charles Cotton as ‘Farmer and Hotel Keeper’, now married to Sarah from Grindon, with a daughter Mary, age 3 [an elder daughter Dorothy was not present on census day]. Sidney remained settled with his family in British Columbia, Canada. Leonard had re-appeared and was described as an ‘Auctioneer’s Clerk’, so presumably was learning his father’s business. Robert does not show up in the 1901 census records, but he was involved with the Boer War in South Africa and went logging in Canada around that time.

In 1911 the census provides the address ‘Springfield House’.

James Oliver, age 75, born 1836, head of household and widower.

Daughter Edith, age 41, born 1870.

Grandson Edgar, age 14, born 1897.

James’ wife Elizabeth Dorothy had died in September 1904. Daughter Edith was recorded on the census form as carrying out ‘housework’, presumably looking after her father, the house, and bringing up Edgar, her son. James’ eldest son Harold was now residing with his family [wife Sarah, daughters Dorothy, age 16, Mary, 13, and Marjorie Alice Barnett, 5] in Staley Cottages; the words ‘Private Means’ are listed under the column headed ‘Occupation’. Sidney was still in British Columbia, but had only a few more years to live; along with two of his sons he was killed in action in France during World War One. The story of Sidney Oliver and his two sons can be read in the World War One folders displayed in St. Giles Church, Hartington. There is no census record for Leonard in 1911, while Robert has re-appeared as a farmer, married to Lavinia Dainton with a young family of three daughters [a fourth came along in 1912] at Moat Hall, Hartington. William had also become a farmer, residing on Dig Street, Hartington, married to Harriet Ann, his second wife; his first wife died in childbirth.

The Story of James Oliver’s Near-shipwreck, 1857.

This remarkable tale, transcribed from James’ original hand-written record, is in diary format, suggesting that some notes at least were written ‘live’. Quite how he managed to have the presence of mind and the physical ability to do this in the appalling conditions in which he found himself seems extraordinary, but it is thought he may have used a pencil; his record book, which still survives in excellent condition, appears to have pencilled words over-written with an ink pen, presumably upon his safe return to dry land. Perhaps he wrote up most of the account while staying for a few days in Plymouth.

The content is exactly as written by James, including occasional words which appear odd to the modern reader such as ‘eat’ instead of ‘ate’. A few words are indecipherable and these are highlighted with an italicised question mark or suggested alternative.

Monday April 6th 1857

Ran down from my lodgings to see at what time the Martin Luther would sail (six o’clock a.m.) was told she would haul out in half an hour. I then started for John Wardle; we got the remainder of our luggage down to the ship (our heavy boxes we got down the day before) this done we went to the provision shop for a barrel of culinary utensils, soap, biscuits, etc. We were there about an hour before we could get served: the people there knowing very well that emigrants are obliged to have these accessories, are in no hurry to oblige them. They are a saucy set of scoundrels. Tom Woodisse came to assist with our luggage. In mistake we took our heavy boxes down into the second cabin; after a deal of haggling we managed to get them on deck, when we were obliged to give a scoundrel of a porter sixpence to sling them down into the steerage. Feeling hungry we went on shore to get some breakfast. When we returned the ship was just hauling off, we ran at the top of our speed, jumped on a plank and scrambled up the ship’s side as best we could; the ship moved as far as the dock gates; then, having gone out the ship remained there until the following morning; we spent most of the day on shore, met Tom Wooddisse and assisted him with his box on board the “Jerry Thompson”, he was fortunate enough to exchange his steerage berth for the second cabin and got a Derbyshire man for a mate, so we left him in good spirits.

We took a stroll on board about four o’clock p.m., they were giving out the week’s provisions; as near as I could guess we received about half the quantity of provisions that we ought to have had, they were served out by an Irish bully, we got neither salt nor vinegar; we crept to our berths about nine o’clock, and slept very comfortably with my carpet bag for a pillow, I slept with my trousers on. The berths are about a yard wide for two adults. J.W. [John Wardle] and I slept in the same berth with a board between. The steerage passengers were composed chiefly of mechanics with a few Irish; they amused themselves with singing, shouting, crooning [?], mewing, bragging [? – braying] and such like accomplishments until near midnight. Rained most of the day.

Tuesday April 7th 1857

Awoke at five, went on deck, we were still at the dock gates, went below and arranged our berths, and drove in some nails to hang our cans on, then went to see if we could get some water boiled, but I found it next to impossible for the small cook house was crowded and so hot that it almost suffocated me; so I went below and munched a biscuit and drank some cold water; this was my first meal on board ship. At twelve o’clock we managed to get some peas and bacon boiled, this made a decent sort of dinner. At six o’clock we got some water boiled, and made some tea to which I eat some pasty I brought with me from home; went to bed at nine, lay a long time awake thinking of home and the old familiar faces I had left behind.

P.S. While we were on deck they took our boxes and provisions barrel into the hold; after some trouble we got the barrel up or we should have been as the Yankees say, “in a fix”. Water given out. I was about three hours before I could get mine, when I got it I found that my can let out the water; I soaped [sealed?] up the crevices as well as I could. Potatoes were served out, we got but a small quantity but the man who examines the tickets, going away for a few minutes, I went a second time and got a few more. I stumbled over a potato bag and helped myself to a few, on the sly of course. The Government Emigration Officer came on board and took one half of the contract tickets. A steam tug towed us into the river about twelve o’clock.

Wednesday April 8th/57

Rose at seven found the ship in the same position as the preceding night, got some tea and biscuits. The Emigration officer came on board again and examined our tickets. Got some salt beef and pork for dinner with some peas porridge. I should scarcely have looked on such a dinner at home but I was hungry and I eat it with a relish. A poor Irishman was hoisted out of his berth; the people said he was covered with vermin, I don’t know whether it was true or not, but they got the poor fellows clothes and dipped them in the sea. Two men went on shore declaring they would not remain in such a pig-sty. I got some peas boiled very nicely while the commissioner was on board. We crept down the hatchway unperceived (the passengers were all ordered on deck) and cooked at our leisure, no one being in the cook house. Went to bed at nine. Rained at intervals.

Thursday April 9th 1857

Rose at seven went on deck, slung a bucket into the sea, got some water, and washed in salt water for the first time, then went to try and get some water boiled, but was about and hour and half in the cook house before it boiled, the fire being low; a fellow deserves a meal after he has been nearly roasted alive, which is the case every time he wants anything cooking. The steam tug came alongside about twelve, the captain came about the same time. The tug towed us a few miles then left us. We lashed our boxes to a post for fear of them being tumbled about should we get into a heavy sea. Made a cake of meal and flour mixed, which was very unpalatable, I eat it to my tea without anything to it. Crept into my berth at nine slept comfortably. Passed the Welsh coast.

Friday April 10th 1857

Awoke at four the passengers’ Steward commenced giving out water at a quarter past, but it was nearly eight o’clock before he called my number, for which I was not in the least sorry; this was the last water we ever got and our can was kind enough to let most of that run out through the holes with which it was studded in the sides and bottom. John got some tea ready about three, I tasted and threw it away for I began to feel squeamish; went on deck soon after and deposited some bile into the sea for the benefit of the fishes. I lay on deck all day in a delightful state of sickness. Sea sickness is a sad leveller of human nature; many faces which I had seen only a few hours before radiant with joy and mirth were now contorted with the various forms and shapes which is the natural consequence of sickness. Though half dead myself I could not refrain from laughing to see the fellows sprawling on deck, then rushing to the side of the vessel in a vomiting fit amid the shouts and laughter of those who were free from it. I went through the performance several times in the course of the day. What time I crept into my berth I do not know; but it was not in the happiest state of mind or body.

Saturday April 11th 1857

Rose about nine, for I was too ill to get any water at four o’clock the time when my number was called. Went and lay on deck until about twelve when a violent and sudden lurch of the ship sent me with many others from the centre of the vessel against the bulwarks with no slight force. I thought if that sort of thing was likely to continue I should be better in my berth, so into my berth I went; after sustaining sundry knocks and bruises on my way, for the vessel began to play at pitch and toss, and it was difficult for a landsman to keep his head from coming in contact with boards etc.

The gale continued to blow all day and night with increasing violence but as yet we were not alarmed for the safety of the ship.

Easter Sunday April 12th

Daylight began to dawn and with it we hoped the wind would abate for we had spent a most uncomfortable night, the ship rolling in a heavy sea. Everything now seemed in confusion, pots and pans, boxes and barrels were pitching from one side of the vessel to the other with a force truly fearful; several efforts were made to fasten the boxes, but it was of no avail. My box and barrel were one of the last to break away. I saw the box breaking away some time before it got loose; when it did get away it went with the force of a steam engine, and I never saw it again until the following Wednesday. Then our provision barrel got free and smashed to pieces scattering cheese, ham, bacon, etc. in various directions but I was too much occupied during this time in keeping myself from going off at the same speed to spend scarcely a passing thought on the destruction of boxes.

Night drew on but the storm rather increased than abated.

We now began to feel some anxiety, the day had been spent in a most wretched manner and darkness would only serve to add fresh horrors to the scene. To complete our misery and “crown our woe” all our berths fell to the ground with a tremendous crash; John and I were on the top row we went bump onto the fellows beneath us who were undoubtedly disagreeably surprised.

After our berths fell, four people were obliged to lie in the same room that had hitherto held only two. Our berths were now six feet long by three in breadth for four adults, we had to lie with our legs over and under one another. My legs were so cramped that I thought I should never have got them into use again.

Imagine above five hundred souls in the dead of the night huddled together in this comfortless state, on the vast ocean, tossed about at the mercy of the mighty waves, with no means of escape, and almost expecting every moment to be the last. Imagination cannot paint the horrors of the scene. Added to the noise of the “rushing mighty winds” and the angry waves, there was the awful din of boxes smashing from one side to the other, anchor chains rattling and noises which would have deafened the Bedlamites; there were some shouting, some crying, some singing, some praying, some swearing, and some few were silent, doubtless thinking of those whom they never expected to see again. When a man sees death almost staring him in the face he thinks rapidly. All the past events of my life seemed to pass in a vision before my eyes in a few moments, all family faces seemed to rise before my mind’s eye, ah! what would I not have given to have been at old Hartington again at that moment; but ‘twas not to be, we had to pass many more wretched hours before our weary eyes were allowed to look upon anything that would save us from a watery grave.

Monday April 13th 1857

“At length the wished for morrow

Broke through the hazy sky”

But though the light of day broke upon us the storm still continued unabated. On the preceding night the fore and maintop gallant [?] masts were carried away. Early on Monday morning one of the sails got adrift and it was deemed advisable to secure it at all risks. The chief mate then ordered some seamen up to secure it, at first some of them refused the dangerous task, when the mate volunteered to go up if the required number would do the same, when one man stepped forward and said he would go up, but “by G- -“ said he “I shall die” seven others followed his example; they went up and while engaged in their duty, the foreyard was carried away; six of the sailors fell into the sea and two fell on deck, one scrambled up the ship’s side out of the water the other five struggled hard for life, but in a few minutes four sank to rise no more, the other, a stout Portugese [sic] was seen battling with the waves for upwards of half an hour; he had divested himself of his clothes with the exception of his boots which he was unable to get off; the poor fellows efforts were unavailing for the sea was running mountains high and no assistance could be rendered, a wave at length hid him from view and he was seen no more.

Soon after the last mentioned catastrophe the main mast was cut away, the mizen [sic] mast falling at the same time, they carried two boats overboard in their fall and stoved in a third.

Efforts were made to get up j?? sails but without success. The M. Luther was now totally unmanageable and drifted rapidly to leeward.

About two o’clock the cook house smashed to pieces, boilers and all the cooking utensils with boiling water were precipitated into the steerage; the noise caused by these rolling about, added to the other uproars was deafening. All this time the ship was rocking from one side to the other, her bulwarks going underwater at every roll so that our heels were one moment where our heads ought to have been, and the next we were standing upright, and so it continued with slight intermission, the shadows of night once more falling thickly around us. Throughout the day we had been led to believe that we should have been in some friendly port or at least near enough to have obtained assistance before nightfall; fallacious hopes that were doomed to be bitterly disappointed: darkness now fell quickly upon us increasing the horrors of our situation ten fold. Sunday night was truly an awful night, but it was faint in comparison to the one now before us – despair was stamped on every countenance – for none of us ever expected to see the blessed light of day. No pen can describe the scenes of misery – no human being can imagine what were the feelings of those on board during this harrowing night. Some were loud in their denunciation of the captain, some of the vessel and some of the owners, some tried to show their coolness by singing songs which always broke down before half finished and some sent up their prayers in silence to Him who alone can rule the wind and the waves.

Sometimes as the ship settled down into the hollow between two waves her motion would cease, and for a few moments everything would be as still as death until another tremendous wave came and tossed her as though she had been a feather. The stench from the accumulation of all kinds of filth was now very offensive and would doubtless have been the cause of disease if we had been compelled to have remained in the ship much longer.

The shrieks of the women and the cries of children were now appalling, every moment we expected to be in the grip of the grim monster – death.

The gurgling waves running close to our heads seemed impatient to swallow us up. Ah! my friends thought I, who are now sleeping in peace on your beds, little do you think what danger now surrounds me; but what will be your grief, if we are doomed to perish, but the die is now cast and a few hours more will either see us safe from the fury of the waves or what is more likely we shall all be plunged into an awful eternity. Night once more passed, the moon began to dawn slowly upon us.

Tuesday April 14th 1857

I crawled on deck as soon as there was sufficient light for a survey of the state of the vessel, and the weather. The wind was slightly abated, but the waves were rolling with unabated fury. It was a sight at once grand, sublime and awful; the ship settling herself for a moment at the base of a mighty wave with billows on every side completely blocking up the view, and seeming ready to fall upon us and with one vast sweep annihilate the brave old vessel, but no; no sooner was the billow upon us than the vessel began slowly to mount the side until she reached the crest of the mountain wave, then for a moment and one moment only you had an unbroken view for miles, but a view that I should never like to witness again from the same situation; as far as the eye could reach the black and angry waves seemed to be lashing each other to fury. Black clouds and blacker waters were all that could be seen from the “tempest tossed barque”.

After scanning the horizon for some time I went below and quietly accommodated myself to the incessant trembling and rocking of the ship.

About half past ten we were startled by a cry which sent the blood coursing through my body with lightning speed; it was a cry neither of land nor breakers (which latter we had been expecting some time) but the cry of a vessel, a steamer bearing down upon us; this joyful news burst upon us like a clap of thunder: when to damp our joy news came soon after to say it was a false statement this was a severe blow, to be passed the prospect of a speedy delivery had raised our spirits immediately to be damped with the bad news directly after.

The first and best news, however, proved to be correct for in about half an hour afterwards a steamer was distinctly seen bearing down upon us. What a shout rent the air when it was clearly seen that the vessel was sailing for us. Few eyes on board but were moistened with the tears of joy. Few but who mentally sent up a prayer of thanksgiving to Him who had thus timely sent us the means of delivery.

The vessel proved to be one of the Oriental Coo. [?] steamers the Tagus from Alexandria for Southampton.

After coming as near to us as was practicable, and the usual preliminaries gone through her captain (Christie) sent one of her boats alongside; our sailors detached two hawsers from our ship but owing to the violence of the waves two hours were consumed before they could be got on board the steamer; which task completed she commenced towing us towards Plymouth which town we reached about noon the following day (Wednesday) where I remained until Saturday and then started for home, where I arrived on the following Monday. Thus ends my first sea voyage.

P.S. When we were taken in tow we were a few miles from the Isle of Ushant and in about six hours more we should have been on the breakers and every soul on board would have perished.

The story of the near-shipwreck and the image of James on the front cover have been reproduced by kind permission of Mrs Janet Oliver.

Production assistance provided by Leon Goodwin.

See www.dippam.ac.uk/ied/records/37383 for additional information.

Hartington History Group – Occasional Paper No. 2 June 2018