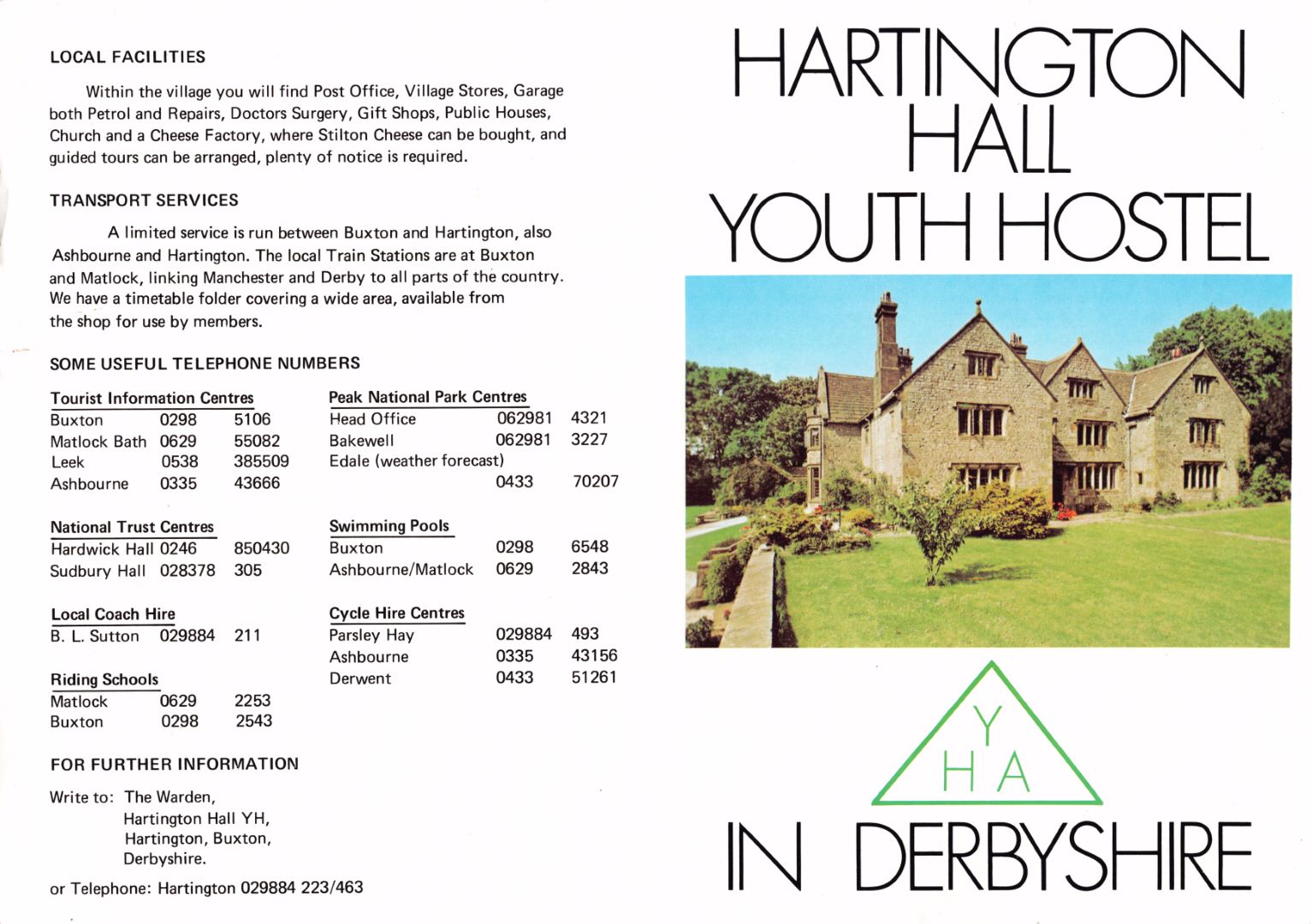

Hartington Hall

Table of Contents

A BRIEF HISTORY OF HARTINGTON HALL |

The original Hartington Hall, prior to 1611, was a simple rectangle in shape and although historians are unsure of the exact date that it was built, some surviving walls exist today which can be dated back to around 1350. Documental evidence is in existence which records that a Robert Bateman was born at the Hall in 1492. This is the first reference connecting the Bateman family to Hartington Hall – a link which continued virtually without break for nearly 6 centuries.

The Hall, which has been built and added to over a long period of time, has been described as a very fine example of a yeomen farmer’s house in the Elizabethan style. It was rebuilt and substantially enlarged in 1611 by Hugh Bateman. This new house was built in a ‘H’ shape with three bays fronting the main road (as it was then). The date of the rebuild is apparent from an inscription on the rain hopper just outside the original front door.

In 1745 it is said that Bonnie Prince Charlie stayed at the Hall during his abortive march south to London to overthrow the Hanoverians. The room on the first floor where he is reputed to have stayed still has the original carved panelling and oak door. Historians unfortunately believe the story to be a romantic fabrication as no firm evidence has been found to support its claim.

Between 1861 and 1866 the Hall was extensively restored by Thomas Osbourne Bateman. The west side of the hall was extended during this period with the south facing elevation of the original hall drastically altered with larger windows added. The main stairway in the house, leading from the stone-floored entrance hall, was built at this titre and Thomas Bateman’s pride in his family seat is illustrated by the stain glass windows etched in the glass at the bottom of the stairs. External matters were not neglected during this massive undertaking with the driveway diverted to sweep around the back of the hall to the stables, coach house and newly built farm.

The third significant development in the history of the Hall occurred in 1911 when Fredrick Bateman continued the expansion. The north and east elevations were built, adding the second staircase to the first floor and finally completing the enclosure of the courtyard. It was during this time that the bay window on the west side was constructed, complete with the Bateman crest and plaque. Fredrick also modernised the internal of the hall during these early years of the 20th century, introducing modem heating systems and electricity throughout.

After Fredrick’s death his son Osbourne inherited Hartington Hall. He spent much of his adult life in Singapore with his mother living alone at the hall until her death in the early 1930’s. Osbourne then leased the building to the YHA

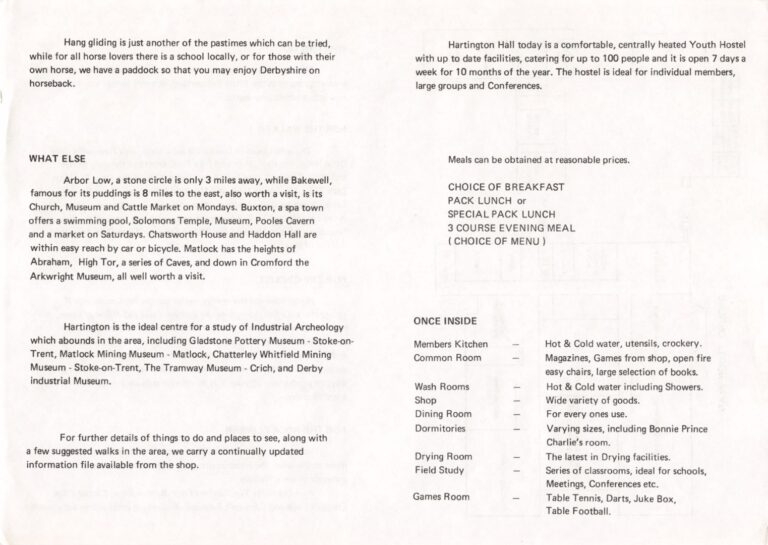

It was one of the most luxurious Youth Hostels in the country with electricity and central heating! It wasn’t quite up to the modem standards of comfortable living however – there was no fresh water, and upon arrival, guests were sent back down the hill with a milkmaids yoke and buckets to collect water from the well in the centre of the village!

In 1934 the first ever meeting of the International Youth Hostel Federation (I.Y.H.F.) took place here at Hartington Hall. The founder of die movement, Richard Schirrmann, planted a Copper Beech tree in the grounds to mark the occasion.

In 1947 YHA. finally bought the Hall after a national appeal. The farm was sold off to the present incumbents, the Sherratt family, at a later date.

Over the years YHA has steadily improved the facilities at the Hall. A major refurbishment occurred in 1987 with the modernisation of the kitchen and dining rooms, the transformation of the third floor attic rooms, and the conversion of The Bam into the associations first ever en-suite rooms. Up to this date, the somewhat derelict barn housed cows!

In 1997/8 these rooms were refurbished with the addition of a further four family en-suite rooms, two smart new study-rooms, an extensive new self-catering complex, laundry and drying room. This was the first phase in a complete re-development of the site. The second stage is the modernisation of the main house which includes the relocation of the staff to a new staff house in the courtyard, the reduction of the large dormitories, the addition of many more toilets and showers, the creation of several more sitting areas, and the relocation of the reception to enable the re-opening of the original front door as the main way into the hall. It goes without saying that the whole hostel is to be refurbished to a very high standard with new furniture and fittings throughout.

This ambitious project includes the restoration of Hartington Hall and it is hoped that help will be forthcoming in the form of a grant from the Heritage Lottery Fund. An application was submitted in January 1998 and it is hoped that the work, which will take approximately 7 months to complete, will begin in September 2001.

HARTINGTON VILLAGE

To fit the Hall into context it would be useful to give a brief background to the village from which Hartington Hall takes its name.

Hartington had strategic importance given its location at the crossing on the River Dove. It had two castles by the thirteenth century, at Pilsbury and Bank Top, indicating that this was a site of some significance. Clive Hart states this is the only example in North Derbyshire of two such castles co-existing, he suggests that “Bank Top was an off shoot of Pilsbury built to defend the planted town of Hartington and to command the Dove Valley”. [1] Both castles were built on lands belonging to the De Ferrers family who owned lands in the north of the Manor.

Traditionally markets grew up around defensive sites and Hartington seems to have been more successful than Pilsbury in this respect. The latter did not thrive and today is much shrunken compared to the medieval settlement. Hartington on the other hand was granted a Royal Charter to hold a market in 1203. By 1614, the Common Pastures map clearly shows the distinctive large triangular market place.[2]

In the seventeenth century Hall Bank was one of the main routes into the village and the 1614 map shows it as being much wider than it is today. It also shows the boundary wall to the Hall, was at this time much closer to the main building. Immediately behind the wall and parallel to it were three outbuildings, between the boundary wall and the road was an area of open grass land. Boundary walls of this older and wider area can still be seen in ruinous form to the south of the road. One building fronting the road to the east of the hall on the 1614 plan still has a gable partly surviving in a garden wall. (The wall now forms the division between the Warden’s bungalow and the main garden. It is particularly noticeable from the upper level of the Warden’s garden). ♦

In the sixteenth century it was fairly common practice to widen a road as an extension of a market place. At Hartington it is more likely that a wider road was needed for cattle drovers coming to market from the Heathcote direction. Just south east of the hall a large circular mere is shown which no doubt assisted with this function. (The road through the Dale which is one of the main routes into the village today was not constructed until at least 100 years later.)

The market at Hartington flourished in the eighteenth century, being well placed to take advantage of the developing turnpike road system (1724-1826). The 1804 Enclosure map

shows the road through the Dale now in place linking Hartington with the Buxton-Ashbourne turnpike. This must have generated a lot of wealth given the number of high-quality buildings in the village which date from this period. Some of the properties which have date stones include The Old School House 1758, Watergap Farm 1766, The Vicarage 1780 and Springfield House 1790. This economic good fortune continued into the early nineteenth century when Bank House 1828 and Nettletor Farm 1830 were built. It culminated with the construction of the impressive Market Hall in 1836.

With the coming of the railways in the 1860’s Hartington acquired a station, albeit one and a half miles to the west of the village at Hulme End. This would no doubt have stimulated the beginnings of Hartington’s tourist trade. The two existing hotels in the village are nineteenth century buildings, or were certainly remodelled then. Tourism is of course the trade on which the present-day Hall now relies on for its existence.

THE BATEMAN FAMILY UP TO 1824

Thomas Bateman – the nineteenth century archaeologist and antiquarian of Lomberdale Hall Middleton by Youlgreave, was part of the same family as the Hartington Bateman’s. He carried out extensive research into the family’s genealogy and was able to trace the paternal line back to William Bateman, Bishop of Norfolk in the fourteenth century.

Bishop Bateman 1350

This is recorded in the Vol. 1 of the College of Arms, London (examined 1822). What he didn’t establish was whether the family had any links with Derbyshire at this time. The earliest known link seems to have come in 1470 with the birth of Robert Bateman at the Hall, This Hall pre-dates the earliest core of the existing house by at least 140 years.

The Bateman Family were essentially yeoman farmers. It is likely that they did well out of the dissolution of the monasteries in the mid-sixteenth century acquiring land from the Minoresses of London who reputedly held lands in the south of the manor of Hartington. The accumulation of land would obviously have increased their wealth and status in the locality. The early Hall however perhaps did not send out the right signals to the rest of the world, for it is recorded that:

“Hugh Bateman of Hartington and Meadow Plack (Place) in Youlgrave……………………………………………………………………………….. Land Steward to

Wm. Cavendish (1st Earl of Devonshire)……………………………………………………………………………….. Built Hartington Hall in 1611.”[3]

Generations of Bateman’s lived at Hartington Hall from the early seventeenth to the nineteenth century, although little more has been noted about them. What does seem clear is that the much-quoted reference to Bonnie Prince Charlie having spent the night at Hartington Hall is probably a fabrication. No firm evidence has been found to support this story, although the Scots army under Prince Charlie did march from Macclesfield to Ashbourne on their route to Derby in December 1745 and may well have followed the valley of the River Dove for much of that route, thus passing close to Hartington.[4] It is interesting that the story first appears in the mid nineteenth century gazetteers. It was common practice in the nineteenth century to romanticise, any exciting historical association. If an association <

did not exist then one could be invented. A well-known local example of this would be Dorothy Vernon’s supposed moonlight elopement from Haddon Hall. This seems the most likely explanation for the origin of the Bonnie Prince Charlie story.

In the nineteenth century the Batemans were still one of the major landowners in the Hartington area and trade directories of the period note that Sir Hugh Bateman but was second only to the Duke of Devonshire in terms of land ownership within Hartington parish. Ji

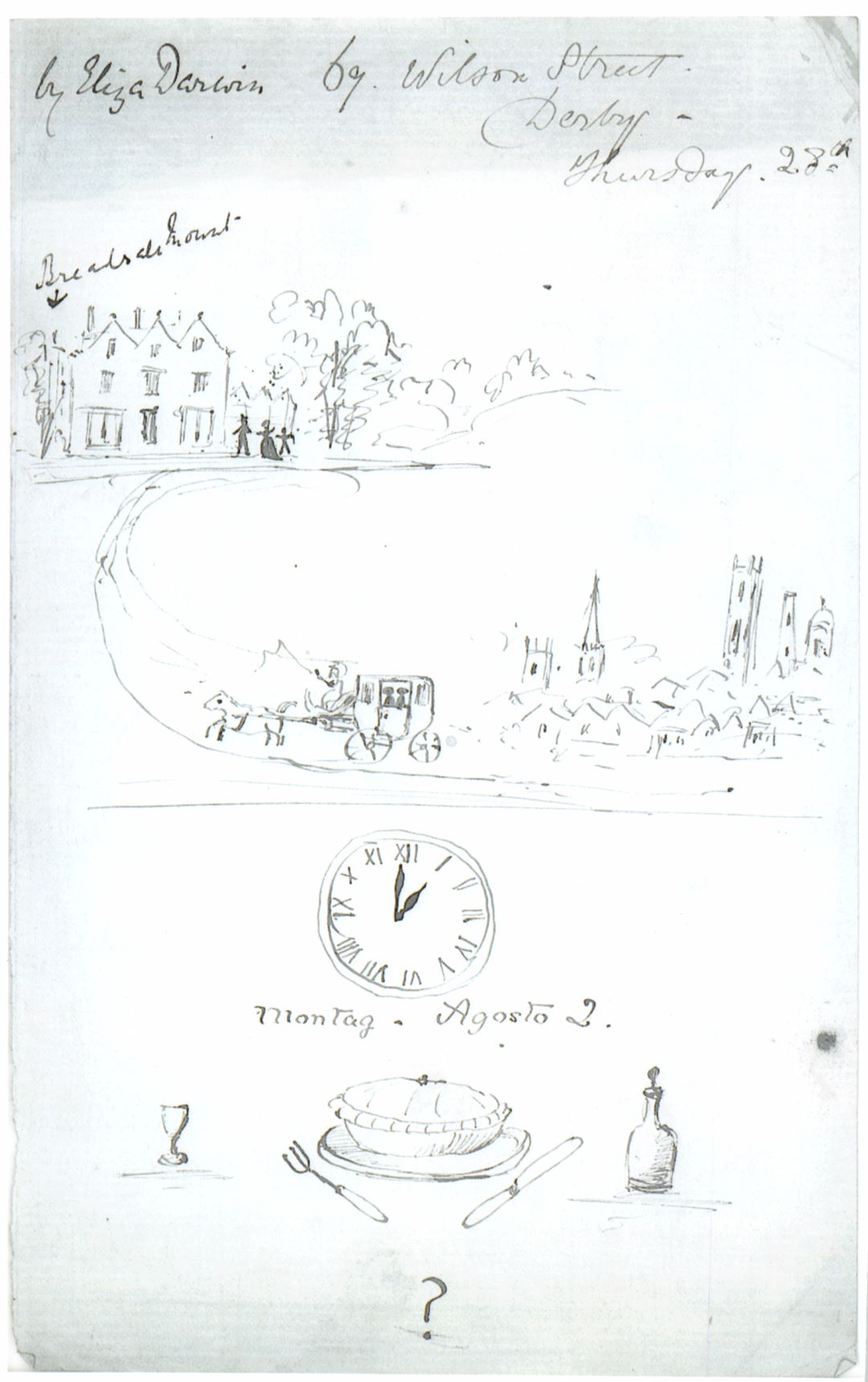

Bank Top and Nettletor Farm are just two examples of local properties owned by the Bateman’s and tenanted out. By the nineteenth century the Bateman’s also held extensive lands in the south of the county near Derby and had another house at Breadsail Mount, possibly acquired through marriage.

It is interesting to note over the centuries the family made several connections by marriage to other notable Derbyshire Families. The names Secheverall (Morley) and Osborne (Derby) FitzHerbert (Tissington) are all represented and become family names. For a family so wealthy and with such good connections it is surprising that so little known about them.

THE BATEMAN FAMILY AFTER 1824

The death of Sir Hugh Bateman in 1824 was a turning point in the history of Hall as he died without a male heir. In his will he left his title of Baronet to Francis Dolman Scott his grandson (the child of his eldest daughter) and his estate was left in trust, with his nephew Richard Bateman as a trustee. The split between the title and the estate no doubt generated some confusion as Burke notes in 1852 that the Hall belonged to the Dolman Scotts. As his grandson lived at Great Barr, Staffordshire and his nephew at Camberwell, Wiltshire, Sir Hugh was effectively the last in the line of Hartington Bateman’s.

Following his death, the Hall was leased to tenants – Richard Bateman evidently remained in Wiltshire as Bagshaw’s Directory of 1846 notes that Thomas Redfern occupied the Hall but that it was the property of the Trustees of Sir Hugh Bateman[5]. When Richard Bateman died in 1853 the estate passed to his son Hugh Willoughby Bateman, also of Camberwell, Wiltshire. He could not have felt any sentimental attachment to the ancestral home as the Hartington estate was sold off in the same year. For the first time since the Hall’s construction in 1611 the hall left the Bateman family’s possession.

It is not certain who the purchaser was, but White’s Directory of 1857 notes that the Hall «

belonged to the Duke of Devonshire and was rented to John Redfern.[6] There is however no record in the Chatsworth House Archives of this purchase having been made. It is clear however that if the Hall did belong to the Devonshire’s it was only very briefly. For whatever reason, but possibly the death of the tenant, the Hall was sold again in 1857 and Thomas Osborne Bateman (Hugh Willoughby’s Uncle) bought the estate, bringing it back into the ownership of Derbyshire branch of the family.

Thomas Osborne was “very well known as an active magistrate, and also by reason of the interest he took in the many public and philanthropic institutions.”[7] However, with his own interests in mind, he set about an extensive programme of building at Hartington Hall between 1859-1866. Apparently, the family home at Breadsall Mount was demolished and the Bateman’s lived at Hartington for approximately 30 years. By the last decade of the nineteenth century however, presumably after Thomas Osborne’s death, the Hall was once

more let to tenants. Certainly, there is no reference to a Bateman living at the Hall between 1890 and 1908.

Tilley in 1890 refers to Edward Dolman Scott (Great Grandson of Sir Hugh Bateman Bt) as residing at the Hall.[8] Bulmer’s Directory 1895 doesn’t mention the name of either Scott or Bateman but simply notes that the Hall was occupied as a farmhouse.[9] Kelly’s Trade Directory in three editions printed between 1899-1904 notes that the Hall was used as a boarding house, but by the time the 1908 edition was published it states that the Hall was the residence of Frederic Osborne FitzHerbert Bateman.

Frederic, who was educated at Oxford, had been a Lieutenant in the Derbyshire Imperial Constabulary before becoming a JP. He inherited the Hall from Thomas Osborne in the early twentieth century and was in residence by 1908. After his death the property passed to his son Osborne Secheverall Bateman who in adult life lived and worked in Singapore. He seems to have spent little time at the Hall, but his mother lived there until the early 1930’s when the decision was taken to lease the property to the Youth Hostels Association.

The Derbyshire Countryside magazine excitedly wrote in its January 1934 edition “… it is — hoped to open it as a youth hostel in good time for Easter with electric light, central heating, fine oak panelling and many examples of magnificent craftsmanship in woodwork and ironwork, it is expected that Hartington Hall will become a great influence on the Youth that will use it.”[10] «

Postcards

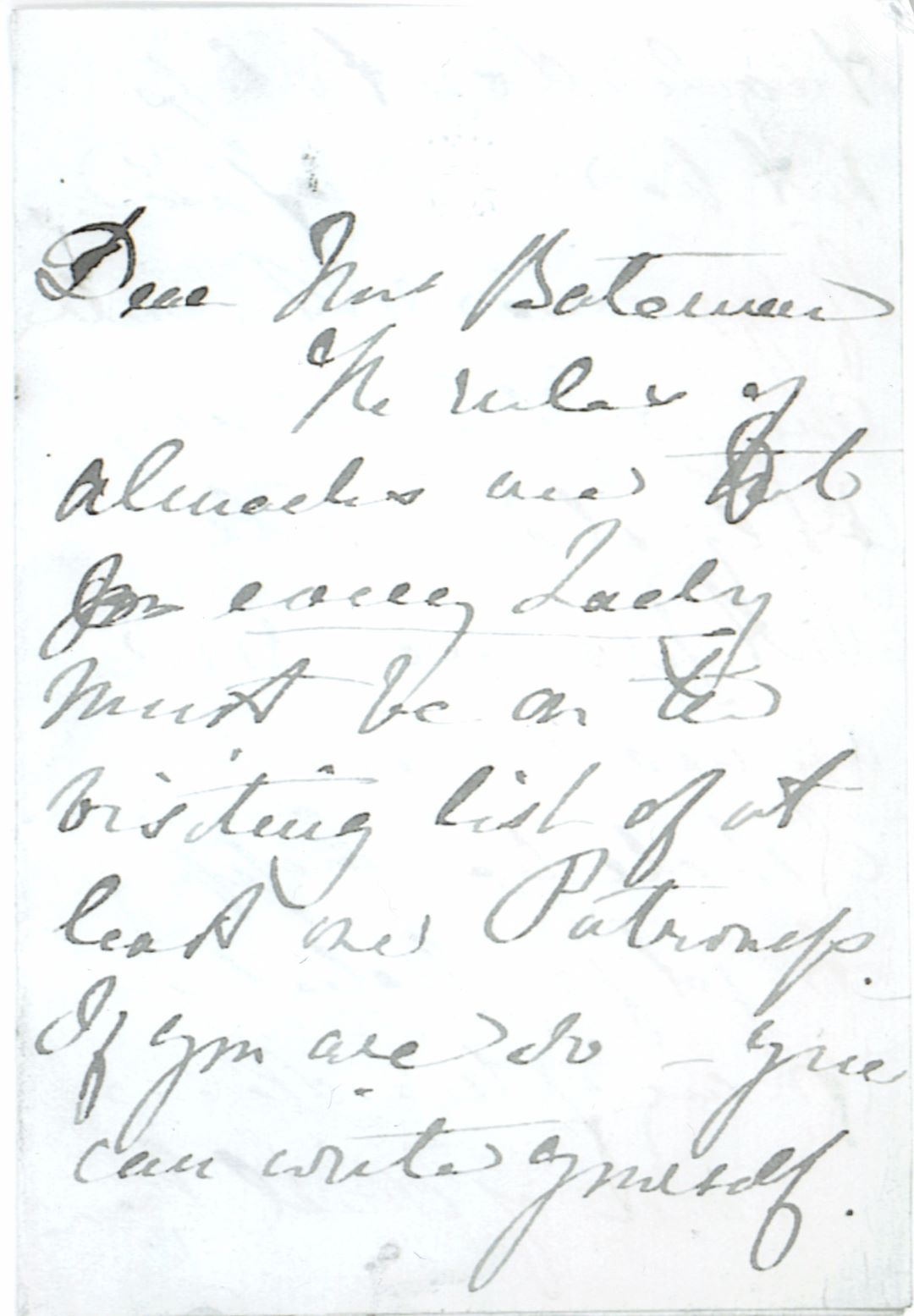

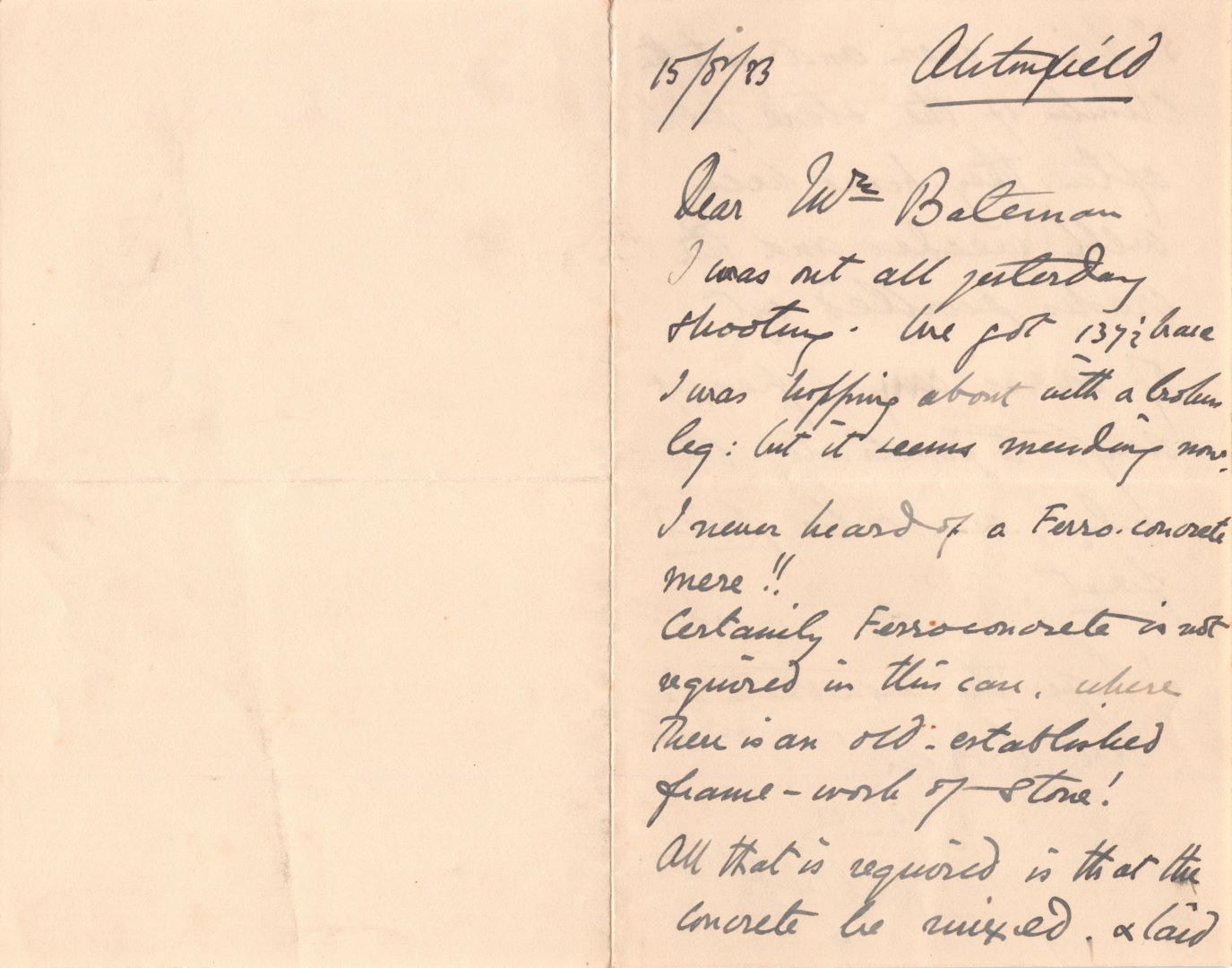

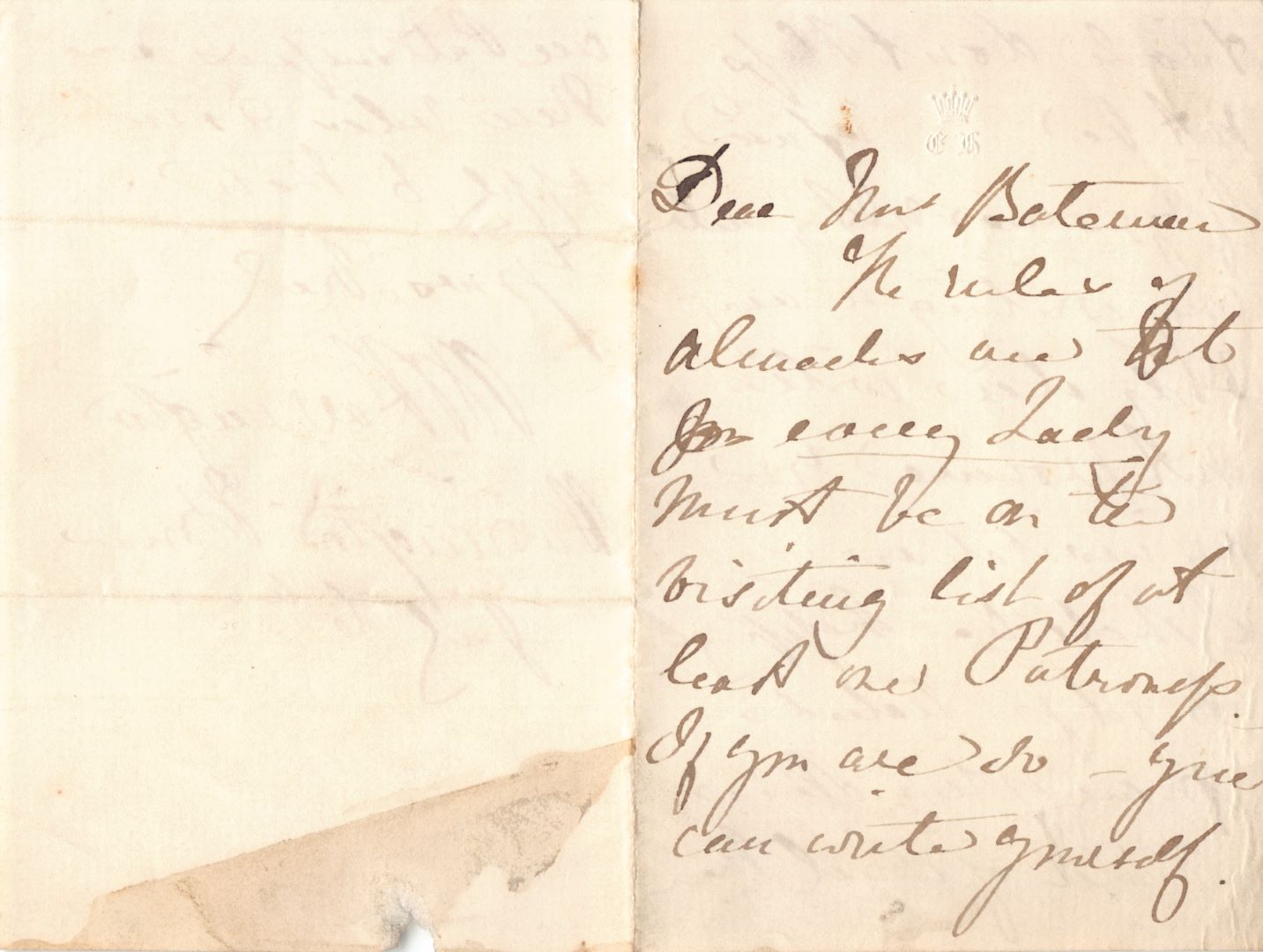

Letters

Other

HISTORIC DEVELOPMENT OF THE BUILDING

The Early Hall (Pre-1611)

As we have seen, the early development of the site is obscure and there is little historical or archaeological evidence available to clarify this. It is alleged that the Poor Clares, Minoresses of London owned lands in the southern part of the manor of Hartington and that they built the first Hall around 1350. The Poor Clares were a Franciscan order “who had a substantial convent in London, another in Northampton, and three in the East Anglian Countryside”.[11] There is no record of any. monastic order living on the site at Hartington Hall, but that is not to say that they did not own lands and property in the area. It could be that the Poor Clares leased the property to the Bateman’s, but there is no record which links the family to the Hall prior to 1470 with the birth of Robert Bateman.

There is a reference which appears in the pedigree of Bateman which states that “John Bateman, of Hertynton, yeoman; purchased lands in the fields of Hertynton, of Nuns-hold, from Richard Hill of Sutton-on-the-Hill, co. Derb. anno 2 H.7 and ob. 17 H. 8,”[12] The dates given refer to John Bateman having been born in the second year of Henry VII’s reign (1487) and having died in the 17th year of Henry Vll’s reign (1526). It is important to note that this reference does not connect either John Bateman or the land he bought to Hartington Hall. It is an important reference however as it implies that some land in the manor of Hartington was in the possession of a religious order, and that it was sold to a member of the Bateman family in the early sixteenth century. It is possible that the Nuns in question were the Poor Clares.

It would be pure speculation to suggest what this early Hall might have looked like. The fact that it was built on top of a hill overlooking the town implies some interest in security but there is no physical or historical evidence to support this. It is known that defences were needed in this area. As well as the two castles at Hartington, C R Hart refers to Moat Hall Farm to the North of the village. This was a house, which as the name suggests, was defended by a moat in the early medieval period[13].

Hartington Hall in the Seventeenth Century

To see the Hall in its proper context it would be useful to have some knowledge of the architectural fashions of the period.

The earliest date found on the Hall is 1611 and this is incorporated on an elaborate rain water hopper head to the east of the main door. This is a date corresponds with a general burst of rebuilding throughout the country which reached its peak between 1590 and 1630. England had been very unstable in the Tudor Period. Overseas, the country had been at war with in France and Spain. At home, the dissolution of the monasteries had led to a great deal of change and upheaval. By the end of Elizabeth I’s reign (1603) the country entered a period of relative peace. This meant that whereas previously, personal fortunes could be compulsorily ploughed into arms for queen and country, they could now be diverted into personal property. The comparatively stable conditions at home were reflected in the style of buildings constructed. Peace meant people had the confidence to build houses without defences- small windows, towers and defendable courtyards were no longer a necessity.

The sixteenth century in Europe had witnessed the Renaissance in art, architecture and philosophy. By the seventeenth century classical styles were well established in Europe but were only just starting to take hold in England. Often classical designs were copied from pattern books, being misinterpreted in the process. In England there was also a curious transitional phase between gothic and classical styles. Typical of this style of building would be the magnificent “prodigy” houses, one of the best examples of which would be Hardwick Hall, Derbyshire by Robert Smythson. The construction of this building began in 1591 and it epitomises the spirit of the age with its famous large windows. Although there is some acknowledgement of the classical style with the symmetrical design and colonnaded entrance it is essential gothic in its perpendicular treatment.

If there was a cultural time lag between the continent and England, then it was much greater between London and the provinces. When Bess of Hardwick built her Hall, she had pretensions to enter into the life of the Royal Court. Although wealthy, Hugh Bateman was not in the same league. However, he may have felt that his position as Land Steward for William Cavendish meant that a new house was needed. Bateman is likely to have been influenced by other country houses of a similar date and the Hall of 1611 shows little awareness of the developing architectural trends other than in its symmetrical plan. The Hall was built in a style typical of a Derbyshire country house in this period. Other local examples can be found at the Offerton Hall, near Hathersage (1550), Stoney Middleton Hall (1600) and Snitterton Hall, South Darley (1631). Unfortunately, neither Hugh Bateman or his wife Margaret lived to enjoy the new Hall for very long. Margaret died in 1612 and Hugh in 1616.

The map of Hartington Common Pastures produced in 1614, by William Heyward, surveyor shows a building of three bays fronting the main road into the village from Heathcote. The outer two bays were gabled to the road with the central bay having a pitched roof lying between the two gables[14] [15].See map 1 p.12.

Evidence from the roof timbers at the present house supports that arrangement. The plan appears as roughly H shaped and evidence from existing walls surveyed for this report supports that view. However, it appears from the detailed survey that one wall of-the 1611 house (and possibly two) incorporates the remains of an earlier house on the site. This is clear from the stonework on the east wall of the present Hall, the ground floor stonework being markedly different from the first floor, the walls marginally thicker, and the existence of a single blocked doorway. The doorway with its very small dimensions and its simple arched head suggests a possible date of late fifteenth century or early sixteenth century. The area adjacent to the doorway appears to have been reconstructed at a later date with differing stone and suggests the removal of an external chimney breast at this location, where an internal fireplace is still located.

The original family landholdings were extensive, and the YHA retain a few areas close to the Hall to this day. The 1614 map shows other properties which also exist to this day, the most 16

notable of which is the small cottage to the west on the roadside. This house which was related to the Hall retains one early mullioned window dating to the same period as the Hall. The plan form with its front door close to its gable end was probably entered alongside the fireplace of the house as built, is also evidence of a seventeenth century date. This property was listed along with many others in the Enclosure of Hartington Parish in 1804 as part of «

Hugh Bateman’s Old Enclosure, and described as simply “House and Homestead”. At that time, the land on which the cottage stood was surrounded by an open area allowing access to other properties to the north. The Enclosure map suggests the start of the narrowing of the roadside area in front of the Hall and its outbuildings, by enclosure of a triangle of land to the south west of the Hall (368 on the Enclosure map). See map appendix 2 ♦

Further extension of the hall grounds towards the road must have been after that date but when this happened is not clear.

Hartington Hall in the Nineteenth Century

There is no surviving documentary evidence which tells us anything about the development of Hall from the time of Hugh Bateman’s death in 1616 until after the death of his descendant Sir Hugh Bateman Bt in 1824. It is unlikely that any alterations were made during the period of tenancy between 1824 and 1857 and the next phase of development comes when Thomas Osborne Bateman bought the Hall and set about remodelling the ancestral home 1861-66.

When the estate was sold in 1853 the sales document includes a map, and this shows that the Hall had evolved from its original H shape to a larger, squarer plan. A description written for this document reads “With the ANCIENT MANSION OF HARTINGTON HALL, approached through a Lawn and Flower Borders; containing Three Attics, Five Family Bed Chambers, and a Dressing Room. A paved Entrance Hall, large Dining Parlor, a Drawing Room, Butler’s Pantry, Kitchen, Scullery, Dairy, Wash-house and Cellars. A Garden and Fruit Walls, Yard, Coal Pen, and Drying ground. Farm Yard, excellent Range of Stone-built Piggeries, Bam, Stables and Outbuildings; also, spacious Bullock Sheds and Yard.’1‘ This gives some idea of how the buildings previously referred to alongside the road, which have long since disappeared were originally used.

In art and architecture, this period marked the end of the gothic revival and the dawning of the arts and crafts movement. Although there were many architectural styles to choose from, the work of architects such as Nesfield and Shaw was gaining popularity. Vernacular building styles were frequently used as sources of inspiration. The skill of the craftsman began to be appreciated as the era of machine-made mass production began. Books such as John Ruskin’s Stones of Venice (1854), and in particular AWN Pugin’s The True Principles of Pointed and Christian Architecture (1841), were very influential. Pugin stressed the importance of using local craftsman and materials. His ideas found great sympathy with all those that mourned the loss of traditional crafts and the English way of life. These nostalgic feelings manifested themselves in many areas of life, and interests such as genealogy, archaeology and history all became popular in the nineteenth century.

There is every indication that these trends found sympathy with Thomas Osborne Bateman. By purchasing Hartington Hall, he was re-establishing his ancestral links which stretched ft

back to the fifteenth century. His new farm buildings showed that this man with a career in the city (he was magistrate) still had an interest in the country life, and the recently constructed railway station at Hartington would have made it easy for him to commute from his rural retreat to his urban employment.

Although a large part of the Hall was rebuilt, the sense of pride in the family’s past was reinforced by the fact that the crests of Osborne, Secheverall and FitzHerbert were reproduced in stained glass and incorporated in the stair window. Also, the farm buildings to the north of the Hall, which we see today, bear the family crest along with the initials of the owner and the 1859 date of construction. (This is visible on a gable close to the rear of the

17 Bateman Scrapbook

Hall). Originally these farm buildings formed a large complex of mainly two storey buildings centred around two yards which were enclosed and sheltered on all but the south side.

Hartington Hall in the Twentieth Century

When Frederic Osborne FitzHerbert Bateman inherited Hartington Hall from his father the country’s feelings of nostalgia for the pre-industrial life were as strong as they had been in his Father’s Day, and for much the same reasons. However, at the turn of the century emotions were heightened as people reflected on what the nineteenth century had brought. The impact of the pace of change should not be underestimated. The majority of the population was now living in towns and Britain had become a manufacturing economy. The rural way *

of life based on agriculture which had existed for centuries was now very much reduced. The Bateman’s themselves no longer made their money from agriculture and much of their farm land had been disposed of in the sales of 1853 and 1857.

It is not surprising that the ancestral home would hold appeal for Frederic. Under his ownership large parts of the Hall were rebuilt, but it seems as if an attempt was made to t

enhance the existing building. He ensured that the building still had a core which was recognisable as dating from 1611. By comparison, at exactly the same time, the new owner of Thornbridge Hall near Bakewell sought to completely redesign his 1860’s house. The resulting hall was a neo Tudor building which gave the impression of great antiquity. At Hartington there was no need to take such radical action but, as at Thornbridge, the opportunity was taken to introduce mod cons such as heating and electricity!

. Frederic Osborne FilsJSerberl ‘Baleman. Fsq’. JF.

Fredric was probably responsible for the further extension of Hartington Hall’s east wing after 1880 as evidenced by the 1st edition OS map. Eventually the central area became an enclosed courtyard by the addition of a range to the north in 1911. The bay window extension is dated 1911 and this appears to be the date for the re-ordering of this part of the building which involved extending out to the west behind the bay and above it. It has not been possible to examine the roof timbers in this area to check the validity of this theory which is based otherwise solely on the evidence of early maps and plans, showing this west range extending straight back from the front range of the house.

Once Osborne Secheverall Bateman inherited the Hall from his father he doesn’t seem to have made any physical alterations to it. His actions however were just as significant in their implications for the Hall. Leasing and eventually selling the Hall to the Youth Hostels Association resulted in the first long standing change of use and ownership for the building since it was built in 1611 and radical alterations to the buildings. For example, the Youth

Hostels Association has now converted part of the range of farm buildings to accommodate its visitors but the remaining portion remains in farm use, related to the land surrounding this side of the village.

GARDENS AND GROUNDS

There is little evidence available to give any indication as to how the gardens and grounds at Hartington Hall might have developed over the centuries. The fact that there is so little information suggests that they were never particularly noteworthy. In the nineteenth century the finest examples of gardens often resulted in a written account or a photograph appearing in publications such as Country Life or The Gardener’s Chronicle. This was not the case for Hartington Hall.

An illustration from William Lawson’s ‘A new Orchard and garden’ (1618). Showing how a garden could be divided into sections with different uses.

The Seventeenth Century

At the time_ Hartington Hall was constructed in 1611, the idea that a garden could offer something more than a purely functional purpose was only just beginning to develop. The first printed texts on the subject included The Gardener’s Labyrinth by Didymus Mountain, 1571, Good and Cheap Husbandry by Gervase Markham in 1614, and A New Orchard and Garden by William Lawson, 1618. All advocated that the garden be divided into compartments. This would typically include a vegetable plot, an orchard, a decorative water feature or fish pond, and a knot garden with herbs for medicinal and culinary uses.

Going on the evidence of the 1614 Common Pastures map it seems that these developing trends had no impact on the grounds at Hartington Hall. It may have been that as the 1614 map was produced so close to the date of the Hall’s construction that the garden hadn’t been laid out by the time Heyward carried out his survey. There is a wall shown on this map running from the north east comer of the Hall to its eastern boundary, and it is possible that this area contained a garden of some sort. Some functional gardening must have been carried out to provide food for the family.

The Nineteenth Century

The 1804 Enclosure map doesn’t show any significant changes to suggest the development of pleasure gardens at the Hall. There is a tighter boundary to its north which runs west-east separating the grounds from the fields overlooking the dale. «

The 1853 sales catalogue for the Hall includes only a brief reference to a lawn and flower borders on the approach to the Hall, presumably this was the area to the south of the front elevation. The sales particulars also refer to a garden and fruit walls, this was probably to the north east of the Hall as the map shows an area of trees contained by walls. These were roughly in the position occupied by the agricultural buildings that we see today.

By the time Thomas Osborne Bateman bought Hartington Hall in 1857 it is unlikely that much time or money had been invested in the gardens, as for 34 years the Hall had been occupied by tenants, not owners. Thomas Osborne spent a lot of money on refurbishing the Hall and erecting new farm buildings and we might reasonably expect that the garden would have been developed to compliment his home. Gardening was very popular in the nineteenth century, there was much interest in both garden design and the new varieties and species of plants that were being introduced. It is very likely that the Hall’s garden was re-developed but we have no evidence to support this until 1880 when the first edition Ordnance Survey was published.

By 1880 Thomas Osborne would have been living at Hartington Hall for around 30 years, and it is likely that any plans he had for the grounds would have been completed by this time.

This map shows that some quite major changes had taken place. The entrance to the drive had been moved further west, and lower down Hall Bank than the original. The new drive was long and curved sweeping round to the back of the house. The original drive was probably reduced in width and paved. As it is today we can see the width of the former entrance gates are much wider than stone path to the south door. *

The area to the west of the new drive contained quite a lot of trees particularly along the western boundary wall, with a prominent clump in the south west corner. The map shows a mixture of conifers and deciduous trees indicating ornamental planting and to the east of the drive a round pond or water feature. To the north of the drive a wall surrounded the area which today contains the flat raised lawn. This area contained more ornamental trees, and the open fronted building which is today used as a cycle store. Perhaps this area provided a sheltered spot for playing lawn games such as croquet, bowls or tennis with a covered area for spectators. Alternatively, it could have been an ornamental garden with the building used as a gazebo. By 1880 the farm buildings had been constructed in the north east comer of the grounds on the site of the former fruit walls and trees. ——————————————————————————

To the east of the Hall the garden had been extended to form a large, square plan with linear paths. According to a former youth hostel warden this garden contained statuary up until the 1930’s, which suggests that it had been a very formal area. The grounds as a whole were set on a west-east axis, they took advantage of the sloping site being terraced on three levels going uphill from west to east. A wall separated the drive from the garden immediately in front of the hall, and second wall divided the front garden from the statuary garden. Stone steps went up from the front garden to the statuary garden and took you to a path which lead to a very large pond near the eastern boundary. The walls, steps and paths are still in existence, although the statues have gone.

Evidence on site today suggests that the gardens could have been refashioned using some of the stone from the demolished outbuildings, the paved area to the south of the Hall contains part of a cheese press, and the odd roof slate. The paths in the warden’s garden are still edged with stone roofing slates and these could have been salvaged from the demolished outbuildings.

Basically, what is shown on the 1880 map is very similar to the layout we see today.

The Twentieth Century

It seems that the last two generations of Bateman’s did very little to alter the garden and only minor changes are evident from the second edition Ordnance Survey map in 1920. The drive had undergone further alterations, the pond to its east is no longer marked and instead, but slightly further north we see an “island” which may have contained ornamental planting. The boundary to the game’s lawn has been removed and the area largely cleared of trees. Also, the sundial is now marked in the south garden.

One feature which is difficult to identify is shown on the map as a roughly circular mark which could be interpreted as a water feature. It is in the approximate position of the rockery seen today in the warden’s garden. Looking at the rockery as it exists now it seems to have been constructed to incorporate a water feature. The sloping site provides a drop which would have lent itself to a waterfall, and the rockery contains a deep central chasm. This feature could have been fed from the large pond to its east. Rockeries were very popular at the turn of the century and this could have been added to the garden by Frederic Bateman when he inherited the Hall.

Quite a few features from the garden’s past can still be identified today, apart from those mentioned above. The garden contains a large number of mature trees along its boundaries, which were probably planted in the mid nineteenth century for Thomas Osborne Bateman. The garden to the west of the Hall contains a good deal of holly, rhododendron and ivy, all of these plants were particularly popular in Victorian gardens. «

Although the two ponds shown on the 1880 ordnance survey map have gone, their locations are still visible. The large pond to the east of the Hall is marked by a large depression in the lawn. The smaller pond to the east of the drive would be roughly in the location of the conifer bed recently planted by the YHA.

Evidence of Earlier Buildings

To the rear of the site in the north west corner of the gardens we see today a wall and a single window exist which are clearly earlier in date than the 1614 map. The window is of a fairly plain section, and shows no sign of ever having been glazed. The central mullion is missing and there are spaces in which bars could have been located during its use, these being single vertical metal bars, one to each side of the mullion, splitting the opening into two and making it difficult to pass through, in the adjacent wall are signs of other openings in the same form, now closed, and also a doorway located more centrally to the range. These are thought to be the remains of the earliest building found on the site, evidence from the present warden is noted which indicates that the walls of this early range exist below ground level on

the access to the wildlife garden, in the form of massive stones buried below the present level of the ground. To the west of the wall and window in the wildlife garden there also appears to be stonework collapsed at the wall base, but very overgrown.

Towards the rear of the hall, the farmyard has another wall in which two small openings of an early date are evident, one seeming to be a window head. As this is close to ground level it is difficult to know what remains are here.

This converted section is marred slightly by poorly proportioned additional first floor windows to the north, and some soil and flue pipes which could have been treated in a more sympathetic manner. One blocked doorway to the north is partly infilled with common blockwork, rather than stone. An opportunity exists to correct some of these points in further works proposed to this range of buildings.

The partial remains of a coach house are situated on the site to the rear of the hall, enclosing a small yard used for deliveries on its north side. To the west of the same space a single storey range used as cycle stores at present exists. This building had a stone slate roof but has recently been re roofed in Staffordshire blue tiles and had coped gables removed from the north end. As the remaining farm buildings have similar tiles over all the roofs this is not too disastrous visually, but confuses the history of the site, as it would seem that this range of buildings probably predated the remaining 1860’s farm complex by some years, and certainly was not built with them as part of the E shaped range. It seems likely that it dated from before the sale of the property in 1853 as it appears on the map enclosed with the catalogue for that sale.

[1] HartC R, p 143

[2] Heyward Common Pastures Map 1614

[3] Bateman Scrapbook

[4] Alison A, p157

[5] Bagshaw T, p 361

[6] White p 417

[7] Gaskill E, p 213-214

[8] Tilley J, p 303

[9] Bulmer, p 383

[10] Derbyshire Countryside p 2

[11] Butler L, Given Wilson C, p 55-56

[12] The Reliquary Vol. 6 1865-6 p 105-108.

[13] Hart, CRp 148

[14] Heyward, Common Pastures Map

[15] enlargement of above map Appendix 3