The Fishing Temple at Beresford Dale

– a famous angling landmark on the banks of the River Dove

PUBLISHED: 09:38 22 March 2016 I UPDATED: 09:38 22 March

2016

By Andrew Griffiths

Charles Cotton’s fishing Temple

Andrew Griffiths visits The Fishing House where Izaak Walton once fished with his young friend and pupil, Charles Cotton

The River Dove in Beresford Dale

Everybody has a home, where things began. For cricketers, it may be Lords. Footballers may say Wembley. If horse racing is your passion, you may think of it as Ascot. And if anglers were looking for such a place, an iconic venue which represented that point where it all began, where the ghosts of the great walk, they could do worse than choose the fishing house on the banks of the River Dove in Beresford Dale.

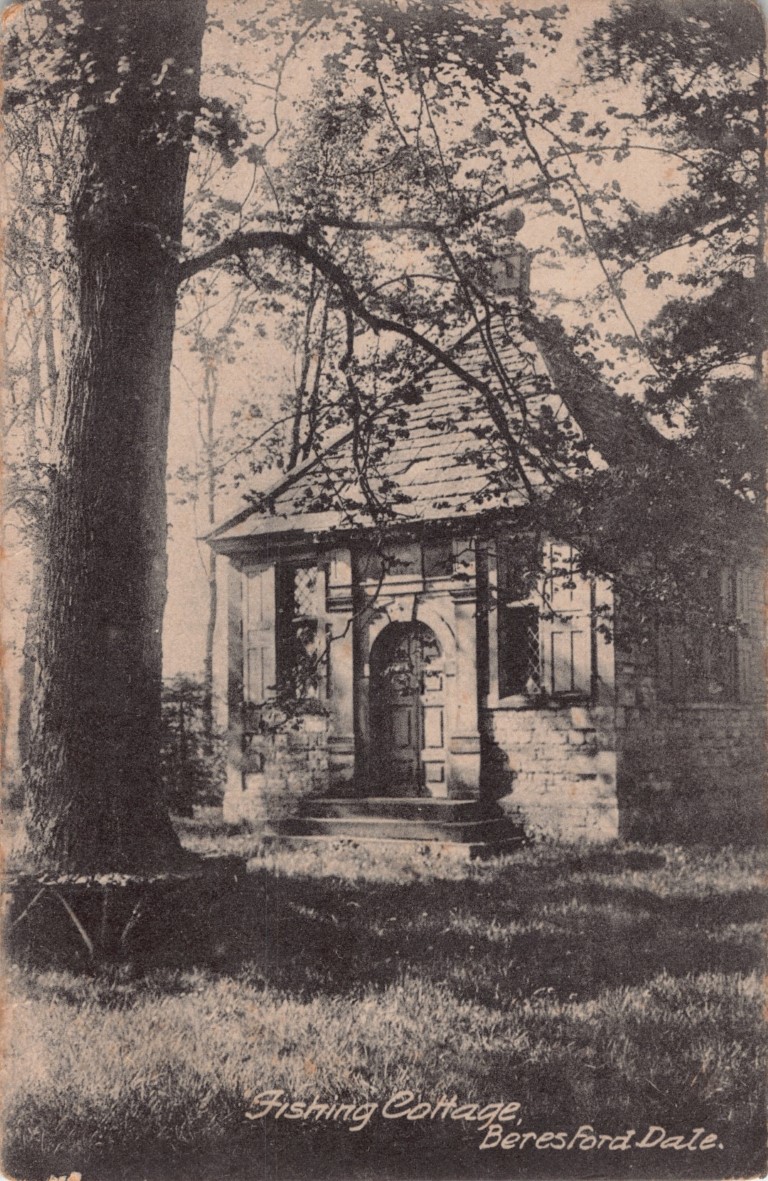

This small house, known as the Temple, stands on private ground but can be glimpsed through trees across the river from the footpath that leads through this sharply sculpted limestone gorge. The higher reaches of the Dove flow through some of the most impressive limestone landscape in the Peak, and there are some contenders.

The Temple is so significant for anglers because it was built by Charles Cotton, a 17th century poet and writer who lived at Beresford Hall, near Hartington. A fanatical fisherman himself, Cotton fished with Izaak Walton, author of The Comp/eat Angler, first published in 1653 and one of the most notable books ever written in the English language. Cotton himself wrote a second section for this book’s later editions based on his experiences of fishing the Dove and it is considered to be one of the finest early treatises on modern fly fishing. Its teachings are still applicable today – some of the fly patterns Cotton describes are still used by modern anglers.

Charles Cotton built the fishing house in 1674 to celebrate his friendship with Izaak Walton and their entwined initials are carved into the stone above the door, along with the inscription: ‘Piscatoribus Sacrum’, a sacred place for anglers, hence it is known in angling circles as ‘The Temple’. The Temple and the Dove feature in Cotton’s writings and represent his idea of angling heaven. This was Cotton’s spiritual home made real.

Charles Cotton’s fishing Temple

Cotton’s fame as a writer of burlesque poetry was enduring, as was his book The Comp/eat Gamester – a treatise on gambling games, which only began to fall out of favour in the early twentieth century. Given his trio of obsessions – raunchy writing, fishing and gambling – it is unsurprising that his later years were beset by financial difficulties and he died penniless in 1687. That’s fishermen for you.

Beresford Hall no longer stands. The Temple has recently been sold, along with the fishing rights to a three mile stretch of the Dove at Beresford, which includes the Temple Beat. The new owner wishes to remain anonymous, which is of course his right, but I can tell you that he works in finance and is an American fund manager based in London.

The Dove rises on Axe Edge moor above Buxton, and forms the boundary between Derbyshire and Staffordshire before joining the Trent at Burton. Summer water levels on the upper Dove have been low for a number of years now, largely due to reduced rainfall, and low water levels concentrate any pollution that is present. The main threat to water quality on the upper Dove has been caused by agricultural run-off.

This pollution source is now being addressed and hopefully the water quality will continue to maintain the steady improvement shown over the last ten years.

The new owner’s intention is to restore the fishery to something Cotton and Walton might recognise. It will be a wild fishery – no fish are stocked, and all fishing is catch and release. This sounds a simple aim, but in practice it means that the river needs to be ‘renaturalised’, so that it will provide a habitat rich in insect life and places of shelter to support fish at all stages of their life cycle.

This takes quite a bit of work.

The man charged with doing this work I can name – he is riverkeeper Stephen Moores, and I met Stephen on a September morning at Beresford for a walk along the river. Stephen calls the rivers he looks after 1home’. He has been a riverkeeper for 37 years, as was his father before him, much of their time spent on the southern chaIk streams of the Test and the Itchen. These are the two rivers that are renowned internationally for their fly fishing, but interestingly, Stephen thinks that the Derbyshire limestone streams now offer the finest wild river fishing in the country.

Stephen has seen fashions come and go in the art and science of the riverkeeper, but is embracing the move towards the wild, self sustaining fishery. As we walk along the riverbank, he points out the work going on to create the right habitat for the wild trout and grayling to spawn successfully and thrive. We stop at an old tree in the middle of the river.

‘This is a tree that fell in,’ he tells me. ‘When I started my career on the chalk streams, I would have been told to remove that, within a day probably. But things have changed totally, and certainly as far as wild fish are concerned, woody debris is the “in” word for river habitat management. So we leave as much as we can in the river, and we have gone full circle and now actually drop trees in the river.’

The ‘woody debris’ serves a number of functions. It breaks up the flow, provides a good breeding ground for the aquatic insects the fish need to eat, and it also offers shelter from predators for small fish.

The relationship between a riverkeeper and his river is an intimate one. Rivers are constantly changing environments and there is nobody better placed than the keeper to monitor those changes over time. Stephen is heavily involved in nature conservation and rings birds for the British Trust for Ornithology.

‘I think of this as my river,’ he says to me, as we walk along its bank. ‘If a keeper doesn’t think that way, he has missed out a lot in his life. All right I haven’t got the deeds for it, but as far as I am concerned, I have always said to any owner that once you have been there for a while it becomes your river.

‘And you should appreciate everything that goes around it. You don’t have to know the name of the plant or the name of the bird or insect necessarily, but if you don’t embrace the whole thing as a river keeper you are missing out, I think, big style.’

The Fishing Temple at Beresford Dale

Inside Cotton’s Temple

I know that Stephen has met our mysterious American financier, whom he tells me is a keen fly fisherman himself. He has already been on the river and caught a couple of trout. I ask Stephen what he thought of him – some might worry that he has bought it to just tuck it away in a portfolio somewhere as an investment, then forget about it.

Stephen doesn’t think so. ‘We were walking along a bit of the river, and he said: “Ah, I love this.” I looked up, thinking to myself that it wasn’t the best bit of water, then he said: “Because it reminds me of the river at home.” It was the river he fishes in New York. This is why he loves it, and I am sure he loves it because of the history. I get the impression he wants to look after it, he wants to enhance it.’

I did get to speak to the new owner over the telephone. A keen fly fisher, he was a history graduate originally, and he has a real sense of the significance of the place. He would like to restore the Temple building, more to how it was in Cotton’s day, but with a few ‘quirks’.

‘One of the things that interests me is how much is on offer locally – food, arts, craftsmen,’ he tells me. ‘Part of the fun would be to have local stonemasons help restore the Temple, and local pottery people making the crockery that goes in the place, and local carpenters making the panelling that replaces Cotton’s original panelling. There is a lot of local interest that can make the Temple and fishery even more charming and unique.’

The purchase of the Temple Beat has been a perfect introduction to our arcane legal system and the tangle of land ownership a long history can bring to light. Access to the Temple has always been restricted due to this patchwork of land ownership, but the new owner is looking forward to working together with his new neighbours.

But for all its beauty and historical significance, the Temple and its river remain unknown to many.

‘I took a couple of people there myself when I was up, and they said: “Oh my god I can’t believe I am actually here, I’ve wanted to come for so long,” and that’s kind of a pity,’ the new owner tells me.

He hopes the fishery will interest a growing number of anglers who share his interest in history and conservation. ·r would like to have fishermen who want to come fish it and are only ever going to fish it once, and balance that with people who do actually value it as their home water, people who will look after it,’ he says.

Back on the river with Stephen Moores, we stop beside Pike Pool, where a shaft of limestone bursts out of the water like a spear. It is one of the most famous locations in angling literature and is described in The Comp/eat Angler. As a fly fisher – or just someone who is interested in history – you cannot fail to be other than a little awed, in the footsteps of Izaak Walton, when the river was bigger and stronger, when Cotton called this water ‘home’.

‘To think that they would have come along here with their willow sticks with a bit of horse hair tied to it and some sort of artificial bait, or even meat or a dead mouse to start with probably,’ says Stephen. ‘It is pretty incredible.’

The restoration of the upper Dove is a work in progress, and the fishing isn’t easy. It is one for the true fly fishing enthusiast who is as concerned with casting back through time to catch something of where it all began as casting out onto the water to winkle out the wild trout and grayling that swim there now.

‘It needs to be maintained and improved so that the fishing and the experience is at the standard of the history,’ the new owner tells me, at the end of our conversation.

Charles Cotton, another wealthy man who became lost in his pursuit of angling, would have surely approved. And look what happened there – what could possibly go wrong?

A Milkmaid’s Song

HAVE YOU READ THIS?

A MILKMAID’S SONG.

Izaak Walton.

This is the tenth of the series of selections from English prose made.by Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch> Professor of English Literature a» Cambridge.

IZAAK WALTON.

—The Compleat Angler.

Izaak Walton (1593-1683), by trade an ironmonger and by recreation a fisherman, was a man of one book, but that a masterpiece. “The Compleat Angler” is not only a complete guide to the psychology of fish and the methods of their capture, but a revelation of its author’s personality like nothing else in literature.

His gentle humour and mellow kindliness are in refreshing contrast to the stormy time in which he lived.

But turn out of the way a little, good Scholar, towards yonder high honeysuckle hedge: there we’ll sit and sing whilst this shower falls so gently upon the teeming earth, and gives yet a sweeter smell to the lovely flowers that adorn these verdant meadows.

Look, under that broad Beech-tree, 1 sat down, when I was last this way a-fishing, and the birds in the adjoining grove seemed to have a friendly contention with an Echo, whose dead voice seemed to live in a hollow cave, near to the brow of that Primrose-hill; there I sat viewing the silver streams glide silently towards their centre, the tempestuous sea; yet, sometimes opposed by rugged roots, and pebble stones, which broke their waves, and turned them into foam: and sometimes I beguiled time by viewing the harmless Lambs, some leaping securely in the cool shade, whilst others sported themselves in the cheerful Sun : and saw others were craving comfort from the swollen udders of their bleating Dams. As I thus sat, these and other sights had so fully possessed my soul with content, that I thought as the Poet has happily expressed it was for that time lifted’above earth;

And possessed joys not promised in my birth.

As I left this place, and entered into the next field, a second pleasure entertained me, ’twas a handsome Milkmaid that had not yet attained so much age and wisdom as to load her mind with any fears of many things that will never be (as too many men too often do), but she cast away all care, and sung like a Nightingale : her voice was good, and the Ditty fitted for it; ’twas that smooth song, which was made by Kit. Marlow, now at least fifty years ago: and the Milkmaid’s Mother sung an answer to it, which was made by Sir Walter Rawleigh in his younger days.

They were old-fashioned Poetry, but choicely good, I think much better than the stronger lines that are now in fashion in this critical age. Look yonder I on my word, yonder they both be a-milking again, I will give her the Chub, and persuade them to sing those two songs to us.

God speed you good woman, 1 have been a-fishing, and am going to Bleak- Hall to my bed, and having caught more fish than will sup myself and my friend I will bestow this upon you and your daughter, for I use to sell none.

Isaac Walton’s Friend

BY J. M. N. JEFFRIES.

BUXTON.

Up here in Derbyshire and in Staffordshire these days it would appear as though fate were playing trick- with tradition and philosophy. Only worthy words and good deeds, say the philosophers, can be immortal; all else is transient as clay.

Two hundred years ago Josiah Wedg¬wood was born and put his trust in clay.

His native district, none the less, is filled with banquets and processions, and is justly ringing with speeches in his honour.

Three hundred years ago Charles Cotton was born and put his trust in words and in at least/ a moiety of good deeds. The second part of one of England’s classic books is written by him. His native district is as quiet and as silent as he left it.

Yet in this, 1 say, there is not

so much contradiction as there seems to be, for both men are being commemorated in the fashion most akin to their achieve-ments. Cotton was a cavalierish sort of 17th- century Burns, often wild in the face of men, always wistful in the face of Nature. He was the companion and the disciple of Isaac Walton, to whose “ Compleat Angler ” he contributed the codicil or second part 1 have mentioned.

How close that companionship was, what feelings Walton entertained for Cotton, those who wish to know may read in that celebrated book, which is within the lazy reach of everybody.

But at least the close of Walton’s dedicatory letter to Cotton’s section of the “Angler” may here be quoted. He had inserted some verses by Cotton into the book and says that if the latter thinks him too bold for doing so, then “ I will so far commute for my offence that though I be more than a hundred miles from you and in the eighty-third year of my age, yet I will forget both and in the next month begin a pilgrimage to beg your pardon, for I would die in your favour, and till then will live, sir, your most affectionate father and friend, Isaac Walton.”

Cotton had long enshrined his affection for the great and good angler by calling him “ father,” though they were quite unrelated, the elder a London linen-draper, the younger a Derbyshire squire. Cotton had the happiness or unhappiness, as people will look upon it, of a mixed character. Besides his pastoral verse he wrote prose in the licentious taste of the world of his day, hid in caves from duns, married a dowager countess for her money, travelled, and cut a brilliant figure.

Once when he was on his way to Ireland, in Chester the mayor of that city was so dazzled by his silks and laces, and particu-larly by a gold belt he wore, that he accosted the fine gentleman and begged him to do the mayoral abode the honour of supping there.

How the world has degenerated! Is there a waistcoat from Savile-row or a tie from the Burlington-arcade which would open the hearth of the Mayor of Chester to-day to a stranger? However, it was the same beruffled hand that lifted hat to the Mayor of Chester which wrote by the banks of the River Dove:

Lord I What good hours do we keep.

How quietly we sleep:

What peace! What unanimity I

And

Here I can eat and sleep and pray

And do more good on one short day

Than he whose whole age outwears

Upon the most conspicuous theatres.

Cotton is not to be misjudged or thought a hypocrite. His truer self angled with Walton by the river. Elsewhere he was distracted, but beside the Dove he was happy; It has been common enough in all periods for those who lived in Courts and amid festivals to affirm their inner devotion to the countryside.

Readers of the “ Compleat Angler ” will learn there how even Queen Elizabeth often wished herself a milkmaid in the month of May. But it is doubtful if cows would ever have shown that combination of being alert and subject which pleased her imperious Majesty.

The month of May meant more than such vague longings to Cotton. He would doff his great puffed fair periwig and stroll down from Beresford Hall, his mortgaged home to the little fishing house he had built by the river with Walton’s and his own initials carved entwined above the door, and there, amid the mayfly, forget real cares and false joys alike.

His troubles were too great for him in the end, alas I He had to flee his Derbyshire dales, and died obscurely in London. The manor house in which he was born fell into ruin and its stones were carted away, but the little fishing-house, built with the mortar of great friendship, still endures by the river bank.

The river, too, flows unchanged, and rising trout every now and then flick open lids in its smooth and sleeping surface as they did 300 years ago. But the account of a brief visit to that tercentenary scene may be allowed to follow this biographical introduction.

Postcards / Photographs / Drawings

DERBYSHIRE JOURNEY—No. 23

By H P CHANNON

Hartington – The Shrine of Anglers

MEMORIES OF COTTON

IT is well nigh 400 years since Charles Cotton and Izaak Walton walked together over the hill to Beresford Dale to spend the day a-fishing in the Dove. Yet Hartington, to-day, remains as faithful to their memory as is । Lichfield to Dr. Johnson and Somerby to Tennyson.

There has been no attempt, praise be, to commercialise this historical association with the disciples of angling in the way that Stratford-on-Avon has made money from Shakespeare or Grasmere has bartered Wordsworth.

But there is no lack of pilgrims for all I that; almost every day during the trout season, you will find a little group of fishermen crowding round the collection of pictures in the Charles Cotton Hotel, to admire and to respect these two great characters who have done more for the literature of angling than Beckford and Surtees have done for foxhunting.

ANGLERS SHRINE

Some of these pictures must be worth a considerable sum. Yet it speaks much for the imagination of the proprietors that no reference to them is made in the advertisements of the hotel.

They form a sort of exclusive shrine at which anglers pay homage, as a prelude or a fitting epilogue to a days sport at the loveliest fishing grounds in the Midlands.

Cotton—-a summary of whose history I gave in last week’s article—was born not two miles away from this hotel in 1630. By that time Walton was 37 and a successful Fleet-street Ironmonger.

By 1645. However, the two were the firmest friends, united by a common passion for fishing and contemporary literature. To the fifth edition of Walton’s “The Compleat Angler,” published in this year, Cotton contributed a priceless treatise on fly-fishing.

In those days Hartington was one of England’s largest parishes, extend¬ing for 16 miles in length and rather more than five miles in width.

WILD COUNTRY

It included within its boundaries some of the wildest stretches of country in Derbyshire, Staffordshire, and Cheshire—bleak moorlands, for in¬stance, like Axe Edge, Black Clough, and Whetstone Ridge, which were shunned even by sheep farmers.

Since then, however, part of the parish has been incorporated in the borough of Buxton and the separate

parishes of Fernilee, Earl Sterndale, Burbage, and Biggin-by-Hartington have been created.

But even today the area of the four townships into which the ecclesiastical parish is divided- the Middle, Quarter, Town Quarter, Upper Quarter, and Nether Quarter have an area of con-siderably more than 10.000 acres. with a population of less than one person to ten acres.

Hartington lies in a shallow valley, formed by rolling hills, gashed by two deep, rocky ravines, through which the two principal approaches to the village run—rather in the manner of the road through Cheddar Gorge. And on the grassy moors, where you may hear the haunting cry of the curlew—more eerie, it always seems to me, than the barn owl’s hoot—are many reminders that people dwelt here before the first page of English history was written.

DRUIDICAL CIRCLE

Three miles away, high on the moors, is that strange Druidical circle. Arbor-low— Stonehenge of Derbyshire—a grim ring of stones where human beings were sacrificed when the rays of the rising sun fell upon them from between two sentinel boulders.

To-day, Hartington is built around a great square with a large duck pond making a barrier at one end of it. There is a venerable-looking parish pump there, too. which is actually no more than 35 years old for it was erected when King Edward VII. was crowned.

The grey stone cottages straggle up the lower slopes of hills and hug the narrow road which runs through the steep dale to the odd toy-like railway station perched on a hill more than a mile away.

Hartington’s principal landowner is His Duke of Devonshire, and the village gives the title of Marquess of Harting¬ton to the Duke’s eldest son.

The early history of Hartington is obscure, but by 1204 the village was sufficiently important for King John

THE VILLAGE OF HARTINGTON.

to grant it a market and a three days’ fair.

Like many other Derbyshire estates, the manor of Hartington passed from the Earl of Derby to the Duchy of Lancaster. and the Earl built a fortified manor house in the parish.

When the Queen of Navarre, who married an Earl of Lancaster, endowed the Minories nunnery on Tower Hill, the church and lands of Hartington were bestowed upon it.

Hartington Hall, formerly the seat of the Bateman family. And erected in 1611, is to-day one of the most attractive youth hostels in England, standing, as it does, at the threshold of Dove¬dale and within easy walking distance of the Manifold Valley and the open moors

In the grounds of the hostel is a copper beech tree planted by Richard Schirrmann in 1934

Schirrmann founded the youth hostel movement in Germany, and the tree is meant as a symbol of peace between the youth of all nations.

12th CENTURY CHURCH

The parish church of St. Giles was built in the middle of the 12th century and has an attractive western tower.

There are several monuments to members of the Bateman family, none of them of great antiquity.

One of the best features of the church is the lovely reredos, made of Derbyshire marbles quarried in the vicinity.

It is a pity that Hartington Church cannot boast a Cotton memorial. The fact is that Cotton’s home—the ancestral home of the Beresford family — is in Staffordshire. Cotton attended with his father—a friend, by the way, of Ben Jonson—the services at Alston- field Church, on the other side of the river, where the Cotton pew may still be seen to-day.

It is my intention to follow the Dove to its source on Axe Edge, which is still in the parish of Hartington, although more than ten miles away.